The forgotten horrors that hide in the Holocaust’s long, dark shadow

In a 1908 pamphlet, the German author Eugene Doctor wrote about the antisemitic hatred driving the Jews westward and fretted that their mass arrival in America would spark an antisemitic wave in their new home. Jews, he lamented, “no longer knew where they should tread or lay their heads.”

If a solution to this Jewish quandary wasn’t found, he warned, the situation in the east would “come to a boil… One fine day, even this [situation] will be swept away, and all we’ll have will be the revival of the old refrain: ‘The Jew must be burned alive.’”

In the summer of 1938, before any German occupier forced their hand, Poland passed a law stripping citizenship from any Jew who hadn’t lived in the country for the previous five years. The Nazis, fearful the move would leave them saddled with now-stateless Polish Jews, rounded up 17,000 of them living on German soil and drove them to the Polish border, where they lived in a kind of stateless limbo, refused entry to either Germany or Poland, until the start of the war.

During the standoff, Poland turned to Britain, the US and the League of Nations demanding that they offer new homes to the unwanted deportees. Poland’s deputy ambassador to London, Count Jan Balinski-Jundzill, warned of the terrible consequences that awaited the Jews if the West refused. Poland would have “only one way of solving the Jewish problem — persecution.”

It was the same story once the war was underway. Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu didn’t need Nazi propagandists to convince him that the Jews were a problem that needed solving. After the Nazi declaration of war on the Soviet Union, he was thrilled by the opportunity offered by the chaos engulfing Europe. “Romania needs to be liberated from this entire colony of bloodsuckers who have drained the life essence from the people,” he declared of the country’s Jews. “The international situation is favorable and we can’t afford to miss the moment.”

As the pressure on the Jews grew, so did Western fear of them flooding in as refugees.

In 1910, when the US had already absorbed some two million East European Jews, New York Immigration Commissioner William Williams ended his annual report with a warning: “The time has come when it is necessary to put aside false sentimentality in dealing with a question of immigration, and to give more consideration to its racial and economic aspects and in deciding what additional immigrants we shall receive, to remember that our first duty is to our country.”

American immigration officials working under Williams began turning back more and more Jews arriving in New York, even as the killings and persecution grew worse back in Eastern Europe. Despite their efforts, the Jews kept coming.

In 1921, the US Congress decided to act. It passed the Emergency Quota Act and then the 1924 Quota Act, severely reducing Jewish immigration from over 120,000 per year to under 3,000 a decade later.

The Holocaust, in other words, was understood by the Nazi leadership as a German solution to a problem felt by all. No one wanted the Jews, all sought ways to be rid of them. It was only when the West closed its doors — when the Jews became, in Hannah Arendt’s words, “undeportable” — that Europeans began to contemplate and even embrace the radical Nazi solution to what many saw as everyone’s shared problem. Millions of people could be snuffed out of existence by the German genocidaires because they were unwanted everywhere and protected by no one.

The Nazis’ many, many helpers

And much of Europe participated.

This is a contentious point in today’s Europe, but a true one nonetheless. Many nations protest that they did not actively join in the murders; few can claim they did not restrict Jews’ lives, persecute them, hand them over to their executioners and prevent survivors from returning to their homes after the war. All took part in the larger cleansing, even if only some took upon themselves the responsibility of direct killing.

There were, of course, countless individual Europeans who risked life and limb to save Jews, and even some political and religious leaders who did so. But these are almost everywhere the exceptions. As eminent historian Saul Friedlander has shown, no major social or political group anywhere in Europe rallied collectively to the Jews’ defense.

The Germans planned and initiated the Holocaust. Germany under the Nazi regime bears what Aly calls the “ultimate culpability” for the genocide. But German efforts could not have succeeded without massive collaboration — and in fact in the few places where such help was denied them, they failed.

In Belgium, the Nazis were able to round up nearly two-thirds of the Jews of Flemish Antwerp (65%), where local police collaborated with the occupiers. In French-speaking Brussels, where officials and citizens refused to help, the Nazis’ success rate was halved (37%).

In Hungary, the government enthusiastically deported 437,000 Jews to Auschwitz in the summer of 1944 in an operation wholly run by Hungarians. But these deportees were rural Yiddish-speaking Jews from the provinces. When the Nazis demanded Budapest’s assimilated, middle-class Jews, the Hungarian government balked. Its refusal left the Nazis helpless to implement any large-scale killing in the capital. Most of Budapest’s Jews would survive the war.

The same pattern emerges in Romania, Bulgaria, Greece and elsewhere. Greek collaboration allowed the Nazis to exterminate the Jews of Salonica, while Greek refusal to help meant the same could not be done to the Jews of Athens. The genocide policy was successful only where locals cooperated.

Alas, locals cooperated in the vast majority of places.

As Aly notes, “When we examine the daily practices of persecution in various countries, we cannot fail to note the ease with which German occupiers were able to enlist local nationalist, national-socialist, and antisemitic movements to serve their ends… There is no way we can comprehend the pace and extent of the Holocaust if we restrict our focus to the German centers of command.”

Unwanted

This long, slow, purposeful destruction of European Jewry — the transformation of Europe into a continent literally uninhabitable to Jews — didn’t begin with the war, and didn’t end with its conclusion.

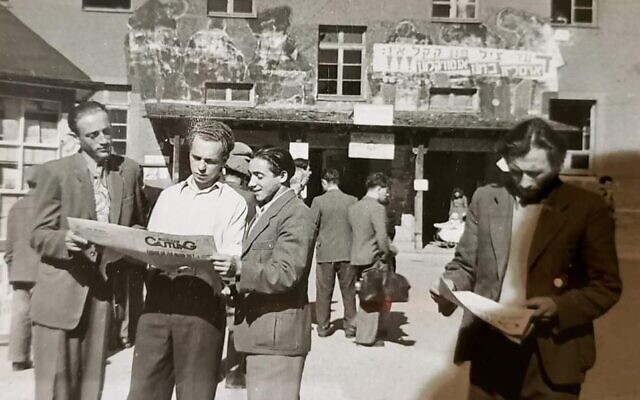

After V-E Day came the now all-but-forgotten story of the Jewish DPs, the “displaced persons” who would languish for years on German soil, imprisoned behind barbed wire by the American and British occupation forces for the simple reason that no one on Earth would take them in.

It was a postscript to the Holocaust that for many survivors encapsulated its deepest truth: That Auschwitz was not the exception to the European Jewish experience but merely its logical conclusion.

On May 8, 1945, the day the war ended, Germany was “in free fall; chaos reigned; national, regional, and local military, police, and political authorities had abandoned their posts,” writes historian David Nasaw. “There was, literally, no one directing traffic, no one policing the streets, no one delivering the mail or picking up the garbage or bringing food to the shops, no one stopping the looting, the rape, the revenge-taking as millions of homeless, ill-clothed, malnourished, disoriented foreigners: Jewish survivors, Polish forced laborers, former Nazi collaborators — all displaced persons — jammed the roadways, the town squares and marketplaces, begging, threatening, desperate.”

This mixed multitude on the roadways of a defeated Germany constituted a “living, moving, pallid wreckage,” Collier’s columnist W. B. Courtney would write as he accompanied the US military drive eastward through the German countryside.

And among these wretched souls, the Jews could be identified with ease, “distinguishable,” writes Nasaw, “by their pallor, emaciated physiques, shaved heads, lice-infested bodies, and the vacant look in their eyes.” They had been the worst treated. All Germany’s slave laborers had suffered. The Jews alone, by order of Hitler’s deputy Heinrich Himmler himself, were deliberately worked to death.

The fall of the Reich left millions of people from across the European continent displaced on German soil. With the war over, the Allies’ first priority was to repatriate anyone who could manage the journey home. At checkpoints throughout Germany, Allied soldiers would collect the wandering millions and deliver them to processing sites established in nearby towns. Millions hitchhiked, stole bicycles or vehicles or simply walked to their former homes in France, Holland, Italy, Belgium, Poland and elsewhere.

By October 1, “more than 2 million Soviets, 1.5 million Frenchmen, 586,000 Italians, 274,000 Dutch citizens, almost 300,000 Belgians and Luxembourgians, more than 200,000 Yugoslavs, 135,000 Czechs, 94,000 Poles, and tens of thousands of other European displaced persons… had been sent home,” writes Nasaw.

Yet as 1945 drew to a close, the Allies came to realize that some of the war’s survivors, who would come to be called “the last million,” could not go home. For one reason or another, they had no home to return to.

Hundreds of thousands of Polish Catholics were afraid of what awaited them in their violence-wracked, Soviet-dominated country. Hundreds of thousands more Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Estonians and Latvians could not return to countries now under Soviet rule because of their active collaboration in the Nazi war effort and occupation regimes.

And then there were the Jews, the survivors of the slave labor camps within Germany and over 200,000 survivors flowing in from the East who had tried returning home and been pushed out by violent neighbors and even pogroms carried out by those who’d felt nothing but relief at their disappearance.

In 1946, the US and Britain established the International Refugee Organization and tasked it with resettling the last million in new homelands. The IRO quickly got to work marketing the remaining DPs to Western and Latin American nations as a solution to the dire shortages of postwar laborers they needed to help rebuild their economies.

It worked. Over the course of 1946, over 700,000 DPs would be offered new homes by IRO member nations — a generosity of spirit that came with one immense caveat.

The first to be plucked from the dismal DP camps were the healthiest and blondest and Protestant: Latvians and Estonians who had mostly spent the war as willing participants in the Nazi war machine. They were prioritized not despite their collaboration with the Nazis but because of it. To Western recruiters, it proved their anti-Communist bona fides. It also had the advantage of leaving them at war’s end healthy and ready to work.

The recruiting nations then turned to the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox DPs, primarily Ukrainians, Poles and Lithuanians who were often unwilling laborers in Nazi war factories but were nevertheless cared for well enough to emerge healthy from the experience.

Then the recruiters swiftly closed up shop and left the camps, leaving behind the last 250,000 DPs to spend the next two years still imprisoned by their erstwhile liberators.

These were, of course, the Jews.

“On May 8, the war in Europe ended,” survivor Hadassah Rosensaft would write in her memoir. “I have often been asked how we felt on that day… Of course, we were glad to hear the news of the Allied victory, but we in [concentration camp-turned-DP camp Bergen] Belsen did not celebrate on that day. For years, I have seen a film on television showing the world’s reaction to the end of the war. In Times Square in New York, in the streets of London and Paris, people were dancing, singing, crying, embracing each other. They were filled with joy that their dear ones would soon come home. Whenever I see that film, I cry. We in Belsen did not dance on that day. We had nothing to be hopeful for. Nobody was waiting for us anywhere. We were alone and abandoned.”

It was no mere oversight that left the Jews trapped in the land of their murderers, and sometimes in the very concentration camps from which they had been “liberated.” It was not ignorance of the problem or the chaos of a frenzied reconstruction that left them ignored by the world as the years passed.

Even as they languished, a frenetic debate was underway in America. Many voices, including Jewish groups and many Christian denominations, called to lift the old quotas and let these last survivors into America. But a coalition of midwestern Republicans and southern Democrats in Congress adamantly refused. The Jews, it was said, were closet communists. Quotas for Eastern Europe, the nations from which the DPs hailed, remained in the immediate post-war period astonishingly low: 6,524 per year from Poland, 386 from Lithuania, 236 from Latvia, and 116 from Estonia.

Congress would finally pass a new displaced-persons bill – though still one that discriminated against Jews – in June 1948, a month after Israel had declared independence and begun to take in the DPs en masse.

The long Holocaust

The Holocaust is too large and complex to allow for only a single narrative of what it means. To the West, including many Western Jews, it is usually understood as a cautionary tale about the terrible results of human intolerance. To drive home this point, teenagers are taken to see museums, death camps and cattle cars.

But a study of the broader context in which the Holocaust took place — the context without which it could not have taken place — upends this easy moral narrative. Auschwitz isn’t an answer to any useful question. Auschwitz is the question.

The answer – one answer – begins to take form only when one steps back from these totems of Holocaust commemoration, from the camp incinerators and Ukrainian killing fields, from the Nazi rallies and the partisan fighters’ resistance poems. It emerges from a close reading of what came before the genocide, the suffering and marginalization that are all but forgotten now, vanished like the millions of murdered souls into the vast shadow cast by what was to come.

The Nazis were less original than anyone wants to admit. The propaganda machines, the anti-Jewish legislation, the fever dream of a Jew-free Europe — in all these the Nazis were copying ideas and policies laid down by others. Where they did innovate, especially in the technology of the genocide, their success depended on the eager collaboration of a great many Europeans in almost every nation and province of the continent.

For all its incomprehensible horror, the focus on the murder itself paradoxically serves as a kind of psychological salve, a way to forget how dozens of nations, including the free Anglophone peoples of the West now host to most of the world’s diaspora Jews — most of them the descendants of those who’d made it into America before 1921 — were unabashed participants in the vast, generations-long corralling of millions of helpless Jews to their ultimate destruction.

The Nazis were ultimately defeated, but not before they’d won their war against the Jews of Europe. It’s a point that might seem monstrous at first glance but becomes unavoidable when one looks at the longer history in which the Holocaust is embedded: To the nations whose Jews were destroyed, that destruction came as a relief. The politics of Europe had been gripped by the Jewish question for three generations, an anxiety that was only removed when the Jews were removed. In Eastern Europe after the war, many surviving Jews were not allowed back to their homes nor treated better than they’d been before. In the West, any meaningful exploration of the broader context and culpability of the nations of Europe and the Anglophone West was quickly set aside in favor of a thin, unthreatening moralism.

Only the Jews are left to remember that when their brethren stood before the open furnace, no other nation or religion, class or institution reached out a hand in rescue. Seven decades of European and Western politics joined in unison to shove them in.